INDEX

On Maria Metsalu

Maria Metsalu's recent performance, "Kultuur," debuted at the SPIELART Theaterfestival last fall before drawing attention at the Copenhagen Toaster Festival at Huset Theater in February. This production unfolds as a homage to the sun, delving into the intimate narrative of a flower and juxtaposing humanity's relentless pursuit of cultivation. In an era where virtually everything is steeped in culture, the Estonian choreographer and performer’s latest work prompts a profound question: amidst our ceaseless drive for calculated progress, is there room for the organic, the untamed, and the unscripted?

"Who loves the Sun? Being sacrificed to the Sun. Sunbathing. Cancer. Abundance. The Sun just gives and gives and gives (...) Sunlight as sanity, science, logic. Sunlight on the ruins in Athens. Sunlight and the ancient world. Sunlight and age stripped the statues of their colors. White marble in the sunlight. The Sun God.” Excerpt from the opening script of Kultuur, co-written by Jaakko Pallasvuo and Maria Metsalu.

In the opening of Maria Metsalu’s latest piece "Kultuur," Metsalu stands alone in the street, pushing a tagged hot dog cart toward the theater, atop thick wood platform boots while wearing a light green and beige sequin bodysuit with a sun at its center. Breathing heavily but methodically, the scene stops a few passersby, curious about its unfolding. Soon, the performer throws herself on the ground, the sound of her boots echoing on the pavement, before escalating the cart, marking pauses and slower movements. Surprised pedestrians and theater-goers alike gather around, drawn by the magnetic pull of her performance. A palpable tension hangs in the air, as onlookers tread carefully, unsure of what to expect next. This is the end of the first scene.

From the Latin "cultura" emerges "kultuur," an Estonian term originally tethered to the nurturing of soil, evolving to encompass the cultivation of intellect and spirit. Across Europe, its dissemination was propelled by the intellectuals of the 18th and 19th centuries, notably during the Age of Enlightenment. This epoch heralded a celebration of knowledge, art, and science, instrumental in shaping modern national identities. Yet, the Enlightenment's ascent paralleled the Industrial Revolution, leading to environmental havoc and societal fractures, as depicted in 2016 by Andreas Malm’s Fossil Capital. Rationality usurped sensation, and Westerners' dominance over nature found expression in grandiose French and English garden designs. This old schism between nature and culture still has a lasting effect on our conception of the world, manifesting in seemingly innocuous acts like the habit of gifting mass-produced flowers, severed from their roots, as a token of affection. In this dichotomy, Metsalu lends voice to the overlooked: a forgotten bedroom flower. Recent revelations of plants' electrical signaling evoke parallels to animal nervous systems, prompting contemplation—might Kultuur be the silent chant of flora, yearning for recognition amidst human clamor?

In her approach, Metsalu sidesteps unnecessary intellectualization, preferring bodily language as a means of communication rather than wordy explanations. The palpable tension in her performances is coupled with a playful spirit, challenging the rigidity of social norms. Drawing from her personal narrative without explicit exposition, Metsalu reveals herself in action. While her work maintains a rehearsed structure, improvisation injects an element of unpredictability. Kultuur evokes the iconic imagery of 1960s performances by Yoko Ono or Carolee Schneemann, pioneers who defied conventional notions of high and low art. In their era, they shattered boundaries, blurring the lines between the raw and the refined, transcending the confines of traditional stage limitations.

@Courtesy of the artist.

Reflecting on her performance, Metsalu recounts, "When I did the piece in Tallinn, every evening a large group of teenagers who I picked up from their usual hangout spot, the mcDonalds, would follow me during the journey with the hot-dog cart towards the theater. Usually they called me out with sexist slurs, tried to grab or punch me as I passed by but I also experienced a big sense of compassion from some of them. One night, I invited two of the teenagers inside the theater to see the piece. Suddenly, their behavior changed. They were all shy and quiet, puzzled by the performance." Metsalu’s work transcends moral considerations. The tension in her pieces, where she at times plays with taboos such as urine, harkens to Ruben Östlund's cinematography, capturing the stark shapes of stilted contemporary art spaces, where the propriety of the structure, i.e., the theater or gallery, clashes with the triviality of her subject, i.e., a pot of flowers, a hot dog cart, organic matter or bodily fluid. It may be why Metsalu’s piece commences outside the theater, in the street, in the everyday, providing a spontaneous spectacle for all, a hallmark of her method of confronting the real and escaping the incestuous confines of the art world.

At the core of Metsalu's work lies a deep sense of engagement, demanding active involvement from her audience. In the second act of the piece, Metsalu takes this interaction to new heights by inviting a guest to join her on stage. Soon, the two are rolling on the ground, compelling other guests to make space. Metsalu's performances consistently exceed expectations; passive audiences need not apply. The presumed act of mere observation quickly transforms into active participation. As Ono famously argued, "Art is not a one-way street. Art is about participation, interaction, and engagement." Dressed as a flower atop a giant pot, Metsalu plays the piano and narrates the story of this captive plant while a guest complicity tags the giant pot.

The night I decided to hit up the Huset theater, my wallet was feeling lighter than usual. Choosing art over a meal, I found myself unexpectedly rewarded with both sustenance and intensity. Kultuur’s last act was no ordinary affair—it was a makeshift “Sun bistro” where five spectators were invited to sit around a bright-yellow table, feasting on oysters, natural wine, and other delicacies prepared by artist Karim Boumjimar, while the rest of the audience watched. This stark separation creates a palpable nervousness in the room, turning part of the audience into the privileged few and the rest into envious, and even voyeuristic observers. The guests become in turn the performers. Metsalu simply argues, “I have always wanted to have a bistro.” Nothing more will be given of her intentions.

As the scene hit its climax, flower-named participants gather around the bright yellow sun totem designed by Nikola Knezevic and Bruno Lillemets. With prayers echoing towards the sun, the performance transforms into a ritual reminiscent of Estonia's midsummer celebration, "jaanipäev." Amidst the lavish feast, a striking juxtaposition emerges against the silent, observing spectators, heightening the tension in the air and prompting both diners and onlookers to confront feelings of exclusion. As the meal nears its end, guests are met with a last twist: the bill. This seemingly mundane act becomes a catalyst for deep discomfort, compelling individuals to peel back their layers of social decorum and reveal their authentic selves in light of this unexpected debt. Soon, all foment an excuse not to pay: speaking first, I offer to do the dishes. What fuels the need to incite guests into action? In an era dominated by individualism and virtual connections, authentic physical engagement and raw emotions are becoming scarce. Our society must shift from Descartes' cogito to the alternative "We feel, therefore we are,'' placing the body and its emotions at the heart of our understanding. Yet, economic disparities, amplified by ultra-capitalism, have widened the chasm between individuals more than ever. While this dinner was merely a performance, with everyone eventually receiving hotdogs, reality is far more unforgiving.

@Courtesy of the artist.

This last part of Metsalu’s performance reminded me of Rirkrit Tiravania’s infamous 1990 dinner installation at the 303 Gallery. Tiravania once said “In the communal act of cooking and eating together, I hope that it is possible to cross physical and imaginary boundaries,” critiquing the sanctity of the art object and Western’s attitude towards life and the living. This comparison might even be intentional. Metsalu is known to embrace ambiguity, much like the visual artist Elain Sturtevant did in the 1970s, whom she greatly admires. Sturtevant blurred the lines between originality and imitation, challenging entrenched notions of authorship and artistic identity.

While Metsalu is known for her solo performances, she also thrives as part of a collective. My initial encounter with her work was in 2023 when the Young Boys Dancing Group (YBDG), which she co-founded in 2014 with Manuel Scheiwiller and Nica Roses, performed at O’Flaherty’s in New York City. The collective had transformed the rear theater of the downtown Manhattan gallery into a slippery performance, using water, soap, and urine to create an intertwined aggregate of human pyramids and deconstructed dance movements. YBDG's members are heirs to a paradigm shift sparked by post-modern dancers in the 1960s and perpetuated through a defiance of norms, influenced by the punk scene of the 1980s and 1990s, where a DIY ethos and a rejection of binaries prevailed.

One night in March, the collective invited me to a bipoc queer circus show in Berlin. As we left the venue, they shared their impressions: “The best part was when everything started to fall apart, the sound sizzling, and the prop stumbling. They should've gone for it.” This sentence sticks in my head, as it perfectly epitomizes the collective’s core: an aversion to perfection and an affinity for chaos. Their stage costumes are usually made from repurposed, tattered garments, thongs, crop tops, bags, and sneakers, while their seemingly simple movements belie a requirement for endurance and precision. Sometimes, props also consist of lighted candles, lasers, or sticks squeezed between buttcheeks, and their stage, a hole of earth on the ground. By methodically partnering with local artists, the YBDG has carved out a space in the alternative art scene, embodying anti-consumerist values and rebuffing normative notions of beauty as dictated by the market. The weird and “what??” becomes a space for endless experimentation.

As I make my way home from Kultuur’s performance, I can't shake the thought: Did the sun revive the flower? And, are collective acts of rituals and bodily connection the cure to all states of desiccation?

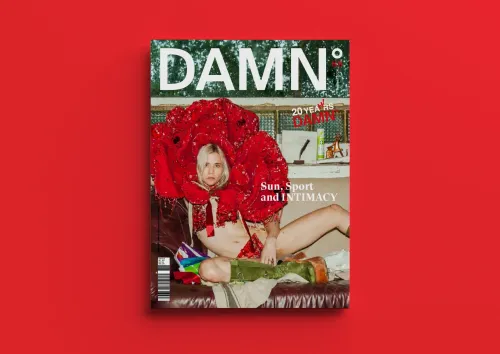

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE ON DAMN MAGAZINE